Brian’s been wondering about SF from other cultures. There’s quite a lot of science fiction written in English by people outside the US, and this has always been the case. People in Britain, Ireland and the Commonwealth have been writing SF for as long as anyone has. (Van Vogt was Canadian, Stapledon and Clarke were British.) But on a panel on non-US anglophone SF at Boreal1 in 2006, we noticed an interesting trend.

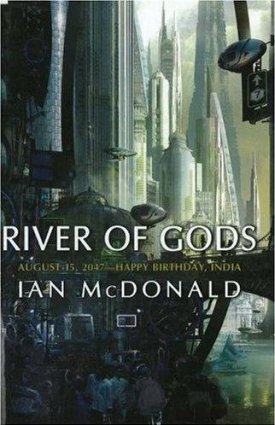

The previous year the Hugo nominees had included Ian McDonald’s River of Gods and that year they included Robert Charles Wilson’s Spin. Geoff Ryman’s Air had just won the Tiptree and the Clarke Award. McDonald is Irish, Wilson and Ryman are Canadian. We naturally mentioned them, because if you’re talking about recent good SF written in English by non-Americans they’re directly relevant, but putting them all together like that another commonality sprang out.

The books are all straight future SF, directly extrapolated futures of this world, futures we can get to from here. River of Gods is set in India, large parts of Spin are set in Indonesia, and Air is set in a future Cambodia. (Since then, McDonald has written Brasyl, and of course he’d already written Chaga, US title Evolution’s Shore, and Kirinya, set in Africa.)

It’s nothing particularly new to set a book in an exotic location. But this isn’t that. In Spin the characters are visiting Americans, but in the others they’re all locals. The places are not treated as exotic, they’re treated science-fictionally, as real places that are going to be there and have their own future.

Science fiction futures typically give one assimilated planetary culture. This isn’t always blandly American, but it often is. I’ve noticed exotic (to me) American details taken as axiomatic—yellow school buses on other planets. I think there was a kind of “planetary melting pot” assumption going on somewhere unconsciously, as when Heinlein made Juan Rico Philipino.

I can certainly think of counter-examples. China Mountain Zhang has a realistically extrapolated China, for instance, and plenty of British writers have unexamined planetary melting-pot futures. But if you have “Space, the final frontier,” you’re immediately buying into all kinds of US ideas about frontiers, whether literally (as in Time Enough For Love) or more metaphorically. I think one of the axioms of Campbellian SF was “The US is going to space,” and indeed in those decades the US was making great leaps in that direction. Even now, SF is mostly published and read in the US. It’s reasonable that it mostly focus on an American future. But if you saw a non-US character, it was probably a token that the US characters had taken along. (I immediately think of the Arabic coffee-drinking guy in The Mote in God’s Eye, who has always bothered me not just for being such a cliche, because it’s supposed to be the twenty-sixth century. Never mind, the Cold War is still going on, too.)

I think paying attention to other countries as real places and setting stories in their real futures is an interesting trend. It isn’t SF coming from those other countries. It’s still SF being written in English by Westerners about them. Fabian Fernandez, a Brazilian SF writer said he wished a Brazilian had written McDonald’s Brasyl.

It also isn’t a subgenre. It doesn’t have a manifesto. I doubt if McDonald and Wilson and Ryman have ever sat down together and planned it—though if they did, I’d love to be a fly on the wall! But it has produced some excellent books, and I’d certainly be interested in any other recent examples.

(1) Boreal is a French-language convention with an English-language programming track. It’s usually in Montreal in May, though there isn’t one next year and in 2010 it’s in Quebec City. Program is done by Christian Sauve, who is one of the people responsible for the French program in next year’s Montreal Worldcon, Anticipation. He always has interesting program ideas, and as there aren’t all that many anglophone program participants at Boreal, I tend to get to discuss a wider range of things than I normally do. At an anglophone convention I tend to be put on panels that bear some relation to what I have written. At Boreal, as here, I get to talk more as a reader. I like that.

Well, I understand what you’re saying but one aspect of the US has been the melting pot. If you’re dealing with a future Earth (or human society) that has successfully united human cultures, the US could be an argueable model.

Also, I’m not a writer but I could imagine that it would be easier to write about a future culture that has more in common with your own culture than it would be to write about a culture based on another culture. I’d hate to write about a future India (for example) because there would be so many ways I could get it wrong.

I guess Gibson started it back in the 80s, when it looked like Japan was going to be the center of the world economy for a while. That didn’t pan out, but the straits the US is in now are rather more dire than then.

Looking at the current trend in world politics, it makes a lot of sense to start trying to imagine what a non-Americentric, multi-polar future will look like. It’s kind of neat that SF writers were a bit ahead of the curve, though.

I think it’s a bit of a stretch to put Spin in the category of non-Amerocentric sf, though. 90% of the story happens in the US, and all of it happens to Americans.

DrakBibliophile @@@@@ 1: “Well, I understand what you’re saying but one aspect of the US has been the melting pot. If you’re dealing with a future Earth (or human society) that has successfully united human cultures, the US could be an argueable model.”

The problem isn’t that sf writers have made that argument, it’s that sf writers have made that argument ad infinitum and in unison, to the point where it’s no longer an argument–only an assumption.

Jo, your list amuses me, because it seems to me to be proof that we Canadians have co-opted you. As I wrote in my Locus article on Canadian SF a few years ago, we tend to have a big tent in Canada. Therefore, if you’re born elsewhere but live here now, you’re Canadian (you, Gibson, Robinson, Wilson). If you’re born in Canada but now live elsewhere, you’re Canadian (Doctorow, van Vogt, Ryman). We even have a special place for writers who were born in the US, spent some time growing up in Canada, and then moved back (Stewart).

All of which goes to prove your point, I think. The border has long since been transcended.

The question that comes to me now is, if there are SF writers practicing their trade in these other countries, who is at fault for not paying attention to them? If I read (to reach back a few years) Achebe, am I reacting to his take on PoCo in a different manner than Nigerians? And does their reaction (or lack thereof) indicate that SF has no or little meaning to them? Does conventional, mundane fiction make for a world that can more easily be related to for people who live in that world? Or is there an escape that they need in their literature that is just different than what we seek out?

We fall down when we don’t seek out these different world views, but the authors (and their publishers) fall down when they don’t bring them to us. The dialogue that could result would be fascinating, I think. I don’t know if the writing or ideas would be mature (I’m not well-read enough to pass judgment), but it seems to me that, at best, this could equate to the “discovery” of Eastern European SF authors. At worst, a contamination that changes those voices before they have a chance to completely develop.

Just a few rambling musings late at night.

D

There are often (but not always) omissions or lacks in representing the culture when an author from one culture writes about another, as well as a different perspective. The omissions might not be noticeable in a future setting, but they are usually apparent in near-future settings. The omissions are likely to disturb me if the time is supposed to be now or near future, but I assume change happens for far future settings. I enjoy reading those SF novels with an exotic feel or a developed alien culture, which often includes ones written by authors who graduated with anthropology degrees.

In addition, when writing about one’s own culture (or a projected adaptation of it), the reader might be able to feel immersed in the culture. In contrast, when writing about another culture, the reader might feel more as if he or she were visiting, rather than actually being part of the culture.

This happens with translations, too. I read some books as a teen that had been translated into English, and later read them in the original French or German. Translators have different philosophies, and some try to perform a more literal translation, while others try to translate into cultural equivalents. If they are trying to make it more culturally “attainable” to the reader, it can lose the exotic flavor, or get more of the “visiting” feel. And, if the translator does not understand the SF genre, important SF elements are sometimes simplified in the translation.

If anyone has any, I would appreciate recommendations of SF from non-US English-speaking countries that was not or only limitedly published in the US or SF novels in French, German, and Spanish, and possibly even Russian (although I would struggle more with that).

LJYoung — Have you read any of the books I mentioned? I really don’t think you’d have that problem with River of Gods or Air. And on the Latin American SF thread, Brazilians are saying that they thought McDonald got their country right in Brasyl. I think the whole point of SF is to make things even more alien than other countries on our own planet seem immersive rather than exotic.

As far as SF in French goes I can recommend Elisabeth Vonarburg, Yves Meynard and Jean-Louis Trudel.

Interesting points. One thing that I would add is that within American SF itself SF from traditionally underrepresented groups such as African-Americans has begun to become much more visible and their own unique perspectives on how the US and the world is have influenced their SF. In addition, there seems to be a backlash against the sort of imperialistic view of how exploration is almost equated with assimilating the “new” or “strange” with “acceptable” value systems (i.e. Anglo-American). It is refreshing to see more and more SF stories influenced by or coming out of post-colonial societies in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Shall be quite interesting to see what will come from these regions in the next decade, as the BRIC nations continue to emerge as economic powers.

I am an Indian writer of SF living in the U.S. You may be interested in my guest blog on Jeff VanderMeer’s site this past October (“In Search of Indian Science Fiction”) where I talked about Indian SF with another Indian SF writer, Anil Menon. Indian SF has a long tradition in Bengali (beginning in the late 1800s) and in a couple of other languages, and there are also a number of Indian SF writers writing in English. Check out the post and discussion at http://www.jeffvandermeer.com/2008/10/07/in-search-of-indian-science-fiction-a-conversation-with-anil-menon/.

Best,

Vandana

Jon Courtenay Grimwood’s Arabesk series is set in a future North Africa, but it is an alternate future in which the Ottoman Empire still exists.

I’ve talked to Ian McDonald about his settings and it is something he’s doing very consciously. I understand that he has at least one more lined up.

Derryl: I think all the writers you mention are as Canadian as possible under the circumstances.

Absolutely, Jo, I don’t disagree. I’m quite proud we have this big tent. It just amuses me.

Now I’m off to read Vandana’s post on Indian SF.

D

I immediately think of the Arabic coffee-drinking guy in The Mote in God’s Eye, who has always bothered me not just for being such a cliche, because it’s supposed to be the twenty-sixth century.

31st or 32nd, I think,but at least the stereotypical conniving Arab had company in the form of a planet full of stereotypical submissive Protestant Scotsmen and a planet full of rascally rebellious Irish. I could make a case that for the time the book was written Bury was at least a bit unusual in that he got lines and had motivation. A lot of SF writers back then relegated the duskier groups to an off-stage role producing the minimum necessary number of people for a catastrophic malthusian collapse.

Just to put Mote into historical context, the issue of Analog where the editor asserted (in response to a comment about Shipwright) that non-whites were only going to get into space by riding on white people’s coat tails so they shouldn’t complain if their colonies are off in the middle of nowhere was if memory serves about five years after Mote was written.

Never mind, the Cold War is still going on, too.

I don’t recall this at all. The Empire is paranoid about the Outies but this conveniently serves to justify any war of conquest the Empire wants to carry out. There’s a more Cold Warish situation at the end of the book, which clearly is meant as a loving tribute to the Truman Doctrine.

Looking at the current trend in world politics, it makes a lot of sense to start trying to imagine what a non-Americentric, multi-polar future will look like

It’s interesting or possibly intensely boring to look at the share of world economic activity to watch how the US has slid from being just over half the planetary economy to about a quarter. This does not reflect errors on the US’s part [1]

so much as the development of once intensely poor regions and the recovery of the major economies that were bombed flat in WWII. The US outspends everyone else put together on military expenditures but it seems clear to me that at some point the size of the US economy relative to everyone else’s summed will make this impractical.

The same thing happened to the UK, of course.

On the plus side from a US point of view, even in a world where every nation is just as rich per person the US will still probably be a major power on the scale of France or Britain during the late Cold War. It’s the third most populous nation in the world, after all, and it has an unusually high birthrate for a developed nation. It wouldn’t be able to dictate international policies the way it does today but it could well be a valuable junior partner for India or China.

Canada in contrast will have the same relative to the world economic throw-weight Phoenix AZ has in the US today. The only reason such an underpopulated nation is in the G-whatever number they are using this week is because so much of the world is so poor.

1: Unless asserting that the decline is because of poor policy will panic the Americans into conceding most of their northern cities to Canada.

The Cassandra Kresnov stories are set in a somewhat Fukuyaman world where every nation in the world eventually adopted the same basic democratic and capitalistic systems, resulting in an Earth where the gap between richest and poorest nations was comparable (or maybe even smaller) than the gap between richest and poorest sub-national regions in a developed nation. It was only after this process ended that the once dominant North American and European nations noticed that this logically meant the center of the planet’s economy was firmly in the Old World, with African and Asian nations greatly outweighing the old powers.

By the time of the novels, a star-nation settled by expats from the US and Europe has set itself up as a rival for the supposedly conservative Earth-centric worlds. Most of the action takes place on a planet settled mainly by South Asians whose skill set includes running what seems to be a pretty nice 100 million plus person multi-ethnic city (At least, it’s nice when people are not committing plot in it). Unfortunately for the protagonist, although the locals are pretty tolerant when it comes to minority groups, she belongs to one that most people dislike and distrust.

Hey thanks for mentioning those! Much appreciated. I always loved the setting of Joel Shepherd’s books for that reason.

Personally, I’m wondering what the election of a biracial president will do for leading roles in fiction, both literary and film/television. I’m optimistic.

Thank you for acquiring North American rights to Paul McAuley’s The Quiet War. Although I don’t know if it is an example of the sort of book we’ve been discussing here, I still want it.

(Nitpick mode, sorry, nothing to do with your main ideas here.) Ryman’s Air is set in Karzistan, a fictional country. It’s The King’s Last Song (recently published in the U.S. by Small Beer) that is set in Cambodia. Both powerful novels.

15

Yep, the setting is most definitely a strength. Shepherd of course is not American either. :)

It’s such a relief to see SF where cities are not run down overpopulated warrens of poverty and crime.

Last year we passed an important milestone where more than half of the human population was urban. People move to cities because even the worst of them offer more hope than life in the country does [1] (Or in some cases, less despair). You wouldn’t know that from most SF, though.

Mind you, I first became away that we were about to become majority urban from a UN report that basically said “People are moving to cities, they do this because of the economic opportunities, cities generally account for a disproportionate fraction of the national economy, and here’s how we can encourage people to stay out in the country.” Anti-city prejudice is pretty common all round.

ObSF: Eric Brown’s Necropath, which is set in the Sea of Bengal in a huge floating city. Unfortunately, how to put this nicely? Despite being a or maybe even the major star port for Earth, Bengal Station adheres to the usual SF conventions as far as large masses of Asian people go, which is to say the numbers may go up but the total wealth never does. The South Asians on Bengal Station provide the pimps, whores, beggars and cops but management appears to be white.

1: Sometimes wild life agrees. As I recall, some Indian primates have gone urban in a major way.

JamesDavisNicoll said: Thank you for acquiring North American rights to Paul McAuley’s The Quiet War. Although I don’t know if it is an example of the sort of book we’ve been discussing here, I still want it.

It is! Very much so, and brilliant. We (we being Pyr books – http://www.pyrsf.com), will most likely publish in the US in Sept or Oct.

Ah, so I should start pestering my shadowy masters in March. Well, resume pestering, since I have been telling them I wanted it since I first heard it was being written.

Any chance that Pyr will collect the ten Quiet War universe short stories into one book?

Intriguing idea. We are collecting all of Ian McDonald’s River of Gods stories in Cyberabad Days out in February.

James @@@@@ 19: to be fair, much of the current migration from country to city is slightly different from the historical norm, in that there aren’t the jobs available in the city either. Instead people stay warehoused in slums surviving in the socalled informal economy.

I just finished The Disposessed, and the Terrans she shows–all two of them–are black-skinned and yellow-skinned, respectively. Shevek even comments on how the Hainish are pale-skinned, like the Urrasti, but unlike the Terrans.

heresiarch @@@@@ 2:

I guess Gibson started it back in the 80s, when it looked like Japan was going to be the center of the world economy for a while.

Didn’t L. Sprague de Camp postulate a Brazilian-dominated future for his Viagens Interplanetarias series, written mostly in the late 1940s and early 1950s? Granted, it was more a background for Planetary Romance adventures than an exercise in Grittily Realistic Extrapolation, but it does indicate an earlier instance of “the future may not be dominated by the US after all”…

A few more random example of SF in non-Western settings:

Gwyneth Jones’ Divine Endurance (set in Malaysia, if I recall correctly)

George Alec Effinger’s Budayeen stories, e.g., When Gravity Fails (Middle Eastern/Arab setting)

Liz Williams’ Empire of Bones (mid-21st Century India)

Martin Wisse @23:

… much of the current migration from country to city is slightly different from the historical norm, in that there aren’t the jobs available in the city either.

I suspect this isn’t really the case, certainly not universally. Much if not most of the migration to cities in China has been driven by manufacturing job growth, for example.

Or, put another way: how do you know that “the historical norm” didn’t involve people moving to cities in the absence of jobs?[1] People might to cities in the past because of famines in the countryside, because of warfare or unrest, or because they had been thrown off of their land by landlords (e.g., enclosure movements in England and Scotland).

[1] If anything, rural inhabitants in the past, lacking things like fast and cheap transport, postal systems, radios, and telephones, might be less likely to know about the economic situation in cities.

The historical norm, as I understand it, was a constant influx of rural workers into the city to replace earlier generations of rural immigrants who had died from disease. City populations weren’t self-supporting until quite recently.

25: Yeah, the US and SU declined rapidly as great powers thanks to WWIII and Brazil stepped into the power vacuum. It’s similar to the back story in H. Beam Piper’s Terro-Human Federation, whose founding powers were a post-WWIII South Africa, Australia and (I think) Argentina.

One of John D. MacDonald’s SF novels (Ballroom of the Skies I think) has a post-WWIII USA that is a junior partner to India, which is locked in a cold war with China. As American culture is copied abroad today, so is Indian culture in this futuristic America (Well, futuristic in the sense that the book was written in 1951 and set in 1979).

Syd Logsdon’a A Fond Farewell to Dying is set well after WWIII flattened Europe and the USA, where the main character is forced to immigrate to India to work in his particular field of research. He is saddled with an unfortunate name, Singer, but he soon changes it to the more reasonable Singh.

PeterErwin @@@@@ 26: True, there were plenty of non-Americentric futures before Gibson. His work still seems important, though. Unlike all the post-WWIII novels mentioned on this thread, Gibson’s irrelevant America wasn’t the result of some future cataclysm, but an extrapolation of then-current trends. Of course, then Japan’s economy and cyberpunk’s popularity tanked, and America moved back to the center. This time around it isn’t a rival chasing the US down, though, it’s the US itself tanking. I’ll bet non-US-centered settings will become the norm, rather than the exception.

Joe Haldeman’s Confederacion setting had a human realm dominated by Hispanophones and Swahiliphones but in that setting the US appears to have simply declined in relation to the other nations rather than having suffered a catastrophic collapse. I think the same is true of Spinrad’s “A Thing of Beauty”, which is one of the earlier stories to use what Herman Kahn called The Coming Japanese Superstate. Oh, and toss in Benford’s In the Ocean of Night, where the newly wealthy Brazilians are buying up US holdings.

Both are from the 1970s, when the US was beset by crises modern readers might find hard to believe, with high fuel prices, high inflation, high unemployment and a Republican administration remarkable for the magnitude of its scandals. A number of authors foresaw a long, inevitable decline for the US (although generally they didn’t stoop to having foreigners are the protagonists).

I didn’t see Linda Nagata’s books, especially Limits of Vision. Taking place predominantly in southeast asia, it gave me a new feel for a place I hadn’t thought about before.